Principe et Action sur les microorganismes

Historique de la stérilisation par lumière pulsée

Les premiers essais de flashs de lumière dans un objectif de décontamination microbiologique datent des années 70 au Japon.

Le premier brevet sur la technologie de lumière pulsée est daté de 1984 (Hiramoto), décrivant l’utilisation de lampes au xénon pour la décontamination microbiologique.

Pendant la période 1990-2000, des laboratoires de recherche ont mené des campagnes d’essais sur une large gamme de produits, aliments, dispositifs médicaux, afin d’évaluer l’efficacité des flashs de lumière pulsée sur la décontamination des surfaces…

Ces études, menées par des microbiologistes, si elles démontraient une efficacité en décontamination, n’ont jamais établi une corrélation entre les paramètres physiques du traitement (puissance du flash, énergie) et son efficacité sur la destruction des microorganismes. Or cette relation « dose-réponse » est indispensable pour le scale-up et la conception d’équipements industriels. Par conséquent la technologie est restée au stade du laboratoire jusqu’aux années 2000.

C’est à cette époque que les premiers essais pour la décontamination des emballages ont eu lieu et que la société Claranor a été créée, en 2004.

La technologie de lumière pulsée Claranor

La technologie de lumière pulsée Claranor est basée sur l’effet germicide de flashs de lumière blanche

Le flash Claranor est produit en 2 étapes :

– Une impulsion de quelques nanosecondes à 20kV permet de rendre la lampe remplie de Xenon conductrice

– Le condensateur chargé à 3000V se décharge dans cet arc au cours d’un pulse de 300 microsecondes, ce qui ionise le gaz de la lampe et génère un plasma émettant une lumière blanche de très forte intensité (20.000 fois la lumière du soleil à la surface de la terre).

Le flash couvre la totalité du spectre de la lumière blanche, tout en étant particulièrement riche en rayons UV, connus pour leur propriétés germicides.

Délivrée sur un laps de temps très court (0,3ms), l’énergie de la lampe produit une puissance de 1MW, dont la moitié est dissipée en chaleur et l’autre en énergie optique. Les UV représentent 20% de cette énergie optique, soit 100kW lors du flash (valeurs approximatives).

Source: Clair and Carlin, 2013, INRA PACA

DESTRUCTION TOTALE DES MICROORGANISMES

L’application d’un ou plusieurs flashs de lumière pulsée sur des microorganismes entraîne leur destruction totale, immédiate, irréversible.

Cette destruction se fonde sur 2 principes :

– la dénaturation des macromolécules du vivant (ADN, protéines de structure et de métabolisme, enzymes) par les UV,

– l’accentuation de cette dénaturation par l’effet puissance de ces UV.

L’efficacité de la technologie a été démontrée sur surface plane (matériau plastique) sur une large variété de microorganismes :

bactéries sous forme végétative mais aussi sporulée (y compris spores thermorésistantes), moisissures, levures, virus.

Le niveau de décontamination atteint dépend de l’intensité du traitement, de la qualité et de la géométrie de la surface à traiter.

Les mécanismes d’action de la technologie sont largement étudiés dans le cadre des collaborations entre Claranor et ses partenaires scientifiques,

en particulier l’INRAE (Institut National de recherche pour l’agriculture, l’alimentation et l’environnement) et le CNRS (Centre National de Recherche Scientifique)

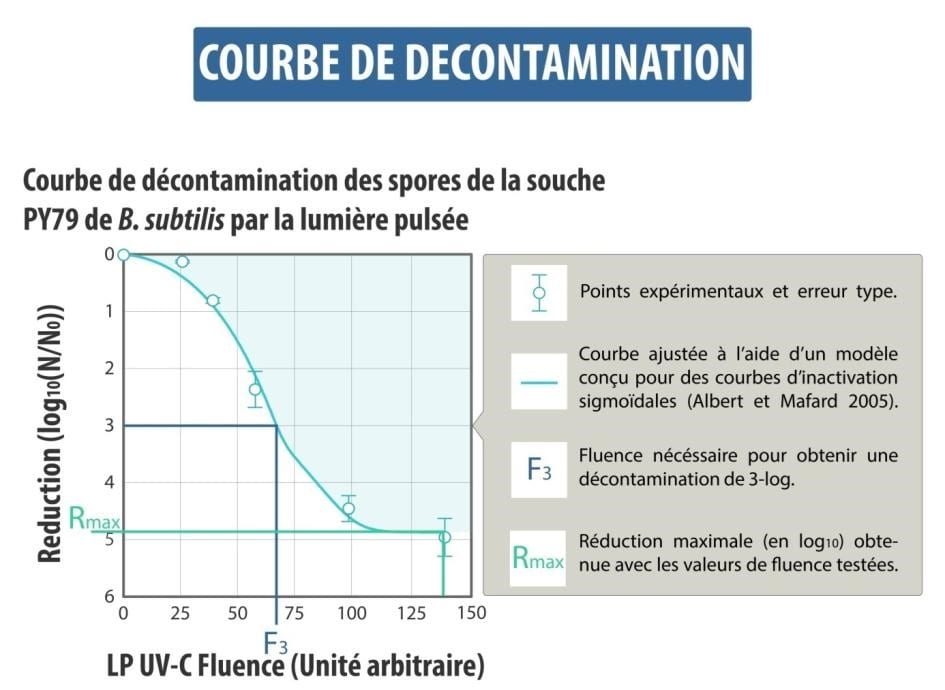

Le travail de thèse (2008 – 2010) réalisé en collaboration entre Claranor et l’Inrae a eu une importance primordiale dans la définition de la relation « dose-réponse », fondations du dimensionnement des équipements Claranor.

UNE QUESTION, UN PROJET, DISCUTEZ AVEC NOTRE EQUIPE DES AVANTAGES DE LA LUMIERE PULSEE

Christophe

Anna

Benjamin

Anthony

Scientific publications:

Claranor-INRA thesis, Caroline Levy : « Principaux facteurs influençant l’efficacité de la Lumière Pulsée pour la décontamination des microorganismes pathogènes et d’altération des denrées alimentaires; »

Role of pigmentation in protecting Aspergillus niger conidiospores against pulsed light radiation.

Esbelin J, Mallea S, J Ram AF, Carlin F (2013). Photochem Photobiol. 2013 May-Jun;89(3):758-61. doi: 10.1111/php.12037. Epub 2013 Jan 29.

The photoprotective potential of fungus pigments was investigated by irradiating conidiospores of three Aspergillus niger strains possessing the same genetic background, but differing in their degree of pigmentation with pulsed light (PL) and monochromatic (254 nm) UV-C radiation.

Spores of A. niger MA93.1 and JHP1.1 presenting, respectively, a fawn and a white pigmentation were more sensitive to PL and continuous UV-C radiation than the wild-type A. niger strain N402 possessing a dark pigment. Both spores of the dark A. niger N402 and the fawn-color mutant were equally resistant to moist heat at 56°C while spores of the white-color mutant were highly sensitive. These results indicate that melanin protects pigmented spores of A. niger from PL.

Decontamination of sugar syrup by pulsed light.

Chaine A, Levy C, Lacour B, Riedel C, Carlin F (2012). J Food Prot. 2012 May;75(5):913-7. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-11-342.

The pulsed light produced by xenon flash lamps was applied to 65 to 67 °Brix sugar syrups artificially contaminated with suspensions of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and with spores of Bacillus subtilis, Geobacillus stearothermophilus, Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris, and Aspergillus niger. The emitted pulsed light contained 18.5 % UV radiation. At least 3-log reductions of S. cerevisiae, B. subtilis, G. stearothermophilus, and A. acidoterrestris suspended in 3-mm-deep volumes of sugar syrup were obtained with a fluence of the incident pulsed light equal to or less than 1.8 J/cm(2), and the same results were obtained for B. subtilis and A. acidoterrestris suspended in 10-mm-deep volumes of sugar syrup.

A. niger spores would require a more intense treatment; for instance, the maximal log reduction was close to 1 with a fluence of the incident pulsed light of 1.2 J/cm(2). A flowthrough reactor with a flow rate of 320 ml/min and a flow gap of 2.15 mm was designed for pulsed light treatment of sugar syrup. Using this device, a 3-log reduction of A. acidoterrestris spores was obtained with 3 to 4 pulses of incident pulsed light at 0.91 J/cm(2) per sugar syrup volume.

Relevant factors affecting microbial surface decontamination by pulsed light.

Levy C, Aubert X, Lacour B, Carlin F (2012). Int J Food Microbiol. 2012 Jan 16;152(3):168-74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.08.022. Epub 2011 Aug 31.

Spores of the psychrotrophic Bacillus cereus KBAB4 strain were produced at 10 °C and 30 °C in fermentors. Spores produced at 30 °C were more resistant to wet heat at 85 °C, 1% glutaraldehyde, 5% hydrogen peroxide, 1M NaOH, and pulsed light at fluences between 0.5 and 1.75 Jcm(-2) and to a lesser extent to monochromatic UV-C at 254 nm. No difference in resistance to 0.25 mM formaldehyde, 1M nitrous acid and 0.025 gl(-1) calcium hypochlorite was observed. Spores produced at 10 °C germinated more efficiently with 10 mM and 100 mM l-alanine than spores produced at 30 °C, while no difference in germination was observed with inosine.

Dipicolinic acid (DPA) content in the spore was significantly higher for spores prepared at 30 °C. The composition of certain fatty acids varied significantly between spores produced at 10 °C and 30 °C.

Deposition of Bacillus subtilis spores using an airbrush-spray or spots to study surface decontamination by pulsed light.

Levy C, Bornard I, Carlin F (2011). J Microbiol Methods. 2011 Feb;84(2):223-7. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.11.021. Epub 2010 Nov 30.

Microbial contamination on surfaces of food processing equipment is a major concern in industries. A new method to inoculate a single-cell layer (monolayer) of microorganisms onto polystyrene was developed, using a deposition with an airbrush. A homogeneous dispersion of Bacillus subtilis DSM 402 spores sprayed on the surface was observed using both plate count and scanning electron microscopy. No clusters were found, even with high spore concentrations (10(7) spores/inoculated surface). A monolayer of microorganisms was also obtained after deposition of 10 μL droplets containing 3×10(4) spores/spot on polystyrene disks, but not with a higher spore concentration.

Pulsed light (PL) applied to monolayers of B. subtilis spores allowed log reductions higher than 6. As a consequence of clusters formation in spots of 10 μL containing more than 3×10(5) spores, log reductions obtained by PL were significantly lower. The comparative advantages of spot and spray depositions were discussed.

Pulsed light for food decontamination: a review

Gómez-López, V.M., Ragaert, P., Debevere, J., and Devlieghere, F.(2007). Trends in Food Science & Technology, 18, 464-473

Pulsed light (PL) is a technique to decontaminate surfaces by killing microorganisms using pulses of an intense broad spectrum, rich in UV-C light.

The present review is focused on the application of PL for food decontamination. It revises the mechanism of microbial inactivation (UV-C as the most important part of the spectrum, photothermal and photochemical mechanisms, inactivation curve, peak power dependence, and photoreactivation), the factors affecting its efficacy, the advantages and problems associated with PL treatment, and results obtained in vitro. Examples of applications to foods are given, including microbial inactivation, and effects on food matrices.

Factors affecting the inactivation of microorganisms by intense light pulses

Gómez-López, V.M., Devlieghere, F., Bonduelle, V., and Debevere, J., (2005). J. Appl. Microbiol. 99: 460-470. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02641.x. PMID:16108787.

AIM : To determine the influence of several factors on the inactivation of micro-organisms by intense light pulses (ILP).

METHODS AND RESULTS : Micro-organisms on agar media were flashed 50 times under different conditions and their inactivation measured. Micro-organisms differed in sensitivity to ILP but no pattern was observed among different groups. Several enumeration methods to quantify the effect of ILP were investigated and showed relevant differences, shading effect and photoreactivation accounted for them, the strike method yielded the most reliable results. Higher decontamination efficiencies were obtained for Petri dishes located close to the strobe and inside the illumination cone.

Decontamination efficacy decreased significantly at contamination levels >6.85 log(10). After 13 successive treatments, no resistance to ILP could be demonstrated. Media warming up depended on the distance from the strobe and the number of flashes.

CONCLUSIONS: For an industrial implementation: the position and orientation of strobes in an unit will determine the lethality, products should be flashed as soon as possible after contamination occurs, a cooling system should be used for heat-sensitive products and flashed products should be light protected. No resistant flora is expected to develop.

SIGNIFICANCE AND IMPACT OF THE STUDY: Conclusions derived from this work will allow a better implementation of this decontamination technique at the industrial level.

Inactivation of polyphenol oxidase by pulsed light

Manzocco L, Panozzo A, Nicoli MC (2013). J Food Sci. 2013 Aug;78(8):E1183-7. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.12216

The effect of pulsed light on the inactivation of polyphenol oxidase (PPO) in model solutions was investigated focusing on the effect of enzyme concentration and total energy dose of the treatment. PPO inactivation increased with the dose of the treatment.

Complete enzyme inactivation was achieved by pulsed light doses higher than 8.75 J cm(-2) . At low PPO concentrations (4 to 10 U), the enzyme resulted in highly inactivated by pulsed light treatment. Further increase in enzyme units determined a progressive decrease in PPO inactivation.

The latter was attributed to protein structural modifications including cleavage and unfolding/aggregation phenomena. PPO amounts higher than 10 U probably favored enzyme conformations that were less prone to intermolecular rearrangements leading to inactivation.